How to harvest honey from a beehive

Did you know that one worker bee makes about an 8th of a teaspoon of honey in its life? Urban beekeeping creates alternatives for the community: local honey, garden pollination throughout the city, and overall perennial greening. The world population of bees is in dramatic decline, and because cities are truly the best place for bees (contrary to popular belief), we do our best to support honey bees by hosting hives around Ontario.

We’re proud to introduce our newest beehive in partnership with Alveole located in Scarborough, Toronto – Minto’s Bendale Beehive! Hosted by one of our employees who works on the Product Development and Sustainability team for Minto Communities, we have direct access to quality photos and information on one of nature’s most amazing pollinators – honey bees.

Minto’s Bendale Beehive is made up of two beehives with over 30,000 bees (and is growing constantly!). In early August 2019, Alveole stopped by for a hive inspection in preparation for the honey harvest (or “extraction”) coming up in September. Here’s what they did:

• Inspected the hives for honey production, brood and hive health

• Located the queen bees to make sure they’re healthy

• Added an additional, third box on top of one of the hives because the bees were so efficient, they needed more space for honey!

So how does honey get extracted from a beehive? And when’s the best time? We’ve got all your honey harvesting facts in this post – because we could all use a bit of sweetness in our lives. If you’re looking for general facts about honey bees in Canada, check out this post to learn more.

Some honey facts just for you, honey

Before we dive into the details – let’s look at some fun facts about bees and honey directly from Alveole:

• In Canada, 75% of honey comes from elsewhere and there’s no say what’s in it – whether it’s blended, cut with corn syrup, or GMO. That’s why relying more heavily on local honey is ideal!

• Each of Montreal’s neighbourhood honeys has a unique colour and taste.

• Urban honey isn’t all polluted – it’s actually the opposite. There are less pesticides in urban honey than there are in certain honeys from the country.

• One worker bee makes about an 8th of a teaspoon of honey in its life.

• An urban beehive makes 10 kg of honey every year (that’s around 22 pounds of honey or almost 30 cups!).

• Honey produced right next to where you live can help with seasonal allergies.

• Pasteurized honey isn’t really honey. It has lost its natural vitamins, enzymes and antioxidants, not to mention most of its taste.

• Bees cover a distance equal to 4 times the circumference of the globe just to produce 1 kg of honey – safe to say, they aren’t lazy!

• Den Garden says that 1 cup of honey is around 1,000 calories (it’s about 64 calories per tablespoon)! Good thing the high quality stuff is rich in antioxidants and is a great alternative for sugar (Honey in coffee? Yes please).

• Honey has been known to have healing properties – according to Den Garden, honey is:

o An anti-inflammatory

o A stimulant for new tissue growth

o An antimicrobial agent

o A provider or quick energy (hello sugar!)

o Helpful for retaining calcium in the body

Now let’s get into the thick of it. How is honey harvested? We’ve got some answers.

Honey extraction 101

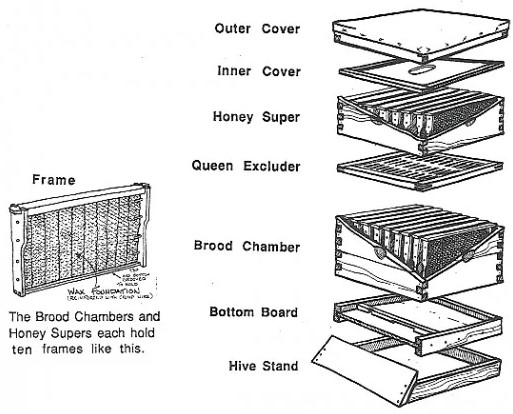

Imagine that one worker bee makes about an 8th of a teaspoon of honey in its life – so crazy! There are a lot of different parts that make up an urban beehive, demonstrated in this diagram by Den Garden:

Den Garden also provides steps for honey extraction that we summarized a bit. Using the above diagram as reference, here they are:

• Step 1: Suit up! Though bees are vegan and don’t sting people intentionally, removing honey frames might agitate them a bit.

• Step 2: Use a bee escape for easy extraction.

o Before removing frames, it’s important to coax bees out of the honey super. A day or so before harvesting honey, place a bee escape in the hole in the inner cover of the hive between the brood chamber and honey super.

o The “bee escape” allows bees to travel in one direction through the device – out of the super for simple honey extraction – perfect.

• Step 3: Remove the frames from the hive.

o Before harvesting honey, the frames (that hold the honey) need to be removed.

o Once the bees are out of the honey super, it gets removed and the frames that are full are taken out. If frames aren’t ¾ full or more, it’s better to leave them in there.

o After making sure the bees left on the frames are removed (carefully, like with a feather, blade of grass, or something natural and soft), place the frames in a plastic tub to transport to the extractor.

• Step 4: Set up your work station. Before extraction begins, certain materials are needed – gather these together and you’re set.

• Step 5: Remove wax cappings from frames. “Capping wax” is the thin layer of new wax that bees build over the top of cured honey – like putting a lid on a jar.

o To remove cappings, start at the top of a frame (holding it vertically), and move a knife (a heated electric knife is easiest!) down the frame over a tub that will collect the wax cappings.

o Fun fact – you can keep wax cappings to make candles, lip balms and lotions!

• Step 6: Extraction time!

o This is where honey is harvested from the frames, filtered and prepared for jars.

o How quickly this process happens depends on how warm the honey is, as warmer honey flows quicker out of the frames.

o Another fun fact – if you don’t have an extractor, you can leave uncapped frames to drip into a bucket overnight (ensuring the room is at least 26.5 degrees Celsius to get the honey flowing).

• Step 7: Bottle it up and admire all the work you and the bees did.

And that’s it! It doesn’t sound like the simplest process ever, but stay tuned for the harvesting we’re doing with Alveole in September – we’ll be sure to post photos and videos.

How do you know when honey is ready to harvest?

We leave it to the experts (Alveole) to tell us when the honey is ready to harvest, but it’s still interesting to learn it for ourselves, too. Apparently, when to harvest honey depends on a variety of factors like location, time of year and of course, the bees.

Some beekeepers harvest regularly several times per year, others watch the hives for signs of readiness and harvest only when they know they can do it safely. So what are the signs? Hobby Farms takes us through 4 ways to know when it’s time:

1. Know your region: Different areas have different “honey flows” – who knew?

2. Know your window: Windows depend on regions, but harvesting too early means you won’t get the full amount of honey you could be getting, and too late means not leaving enough for the colony for winter.

3. Know your honey: There’s a process that bees go through when turning raw nectar into honey, requiring enzymes from the bees, their efforts in storing and fanning it, and time. Once this process is complete, they cap the combs and you know it’s ready for harvest.

4. Know your bees: It’s important to get intimate with your hives and their needs – which is why Alveole checks in with Minto’s Bendale Beehive monthly (at least). Beekeepers pay attention to the signs of harvesting and know to leave 40-60 pounds of honey on the hive to get the bees through the winter.

Up close and personal

We have a ton of amazing photos from Minto’s Bendale Beehive taken by Carl, who’s hosting the hives in his backyard. Between close-ups of bees carrying honey back to the hives and seeing how packed the frames get with bees, they’re unbelievable – so we had to share!

Turns out, honey bees are actually really cute in real life. Not just in cartoons!

Up-close and personal with the Queen – how amazing is the hexagonal shape of the hives?

“All worker bees are female and make up about 90% of the hive. They live only 30-45 days during the summer and do almost all of the work within the hive. They have 7 key responsibilities which include (1) cleaning and preparing cells for larvae, (2) feeding larvae honey, nectar and royal jelly, (3) taking care of the Queen, (4) producing wax to make honeycomb, (5) beating their wings to ventilate the hive and regulate temperature, (6) act as security at the entrance, (7) and will forage flowers for nectar, pollen and propolis up to 5 km away from the hive. They will shift between these duties as the needs of the hive change.” – Carl Pawlowski (@pawlowski.outdoors)

“Honey bees have only ever been observed creating hexagonal honeycomb – because it’s the most spatially efficient shape, requires the least effort and materials while maintaining strength. Here a worker bee is among a frame of uncapped honeycomb.” – Carl Pawlowski (@pawlowski.outdoors)

“A forager returning to the hive with its ‘saddlebags’ full of pollen. Honeybees search up to 5 km from the hive and will keep doing so until they die from fatigue at the end of their life after 30-45 days. One forager can produce 1/8th of a teaspoon of honey in their life.” – Carl Pawlowski (@pawlowski.outdoors)

Honey bees capping the cured honey. “Altruistic to the core, bees dedicate their lives to the well-being of the colony.” – Alveole

Thanks for learning about honey harvesting with us! If you want to stay informed on Minto’s Bendale Beehive, follow Carl on Instagram (@pawlowski.outdoors) and keep watch on our Instagram and blog, as we’ll be posting videos, photos and more fun facts and updates on these amazing, natural pollinators.